Storytelling 101: The Dan Harmon Story Circle

- What is the Dan Harmon Story Circle?

- The Story Circle in story structure theory

- The 8 steps of the story circle

- How to use Dan Harmon’s Story Circle

The Story Circle by Dan Harmon is a basic narrative structure that writers can use to structure and test their story ideas. Telling stories is an inherently human thing, but how we structure the narrative separates a good story from a truly great one.

Because of Dan Harmon’s background in screenwriting, the Story Circle is popular among filmmakers and writers on TV shows and TV series, but any storyteller can benefit from using it. Let’s look at this narrative structure more closely, examine the eight steps, and discuss its use in story and character development!

What is the Dan Harmon Story Circle?

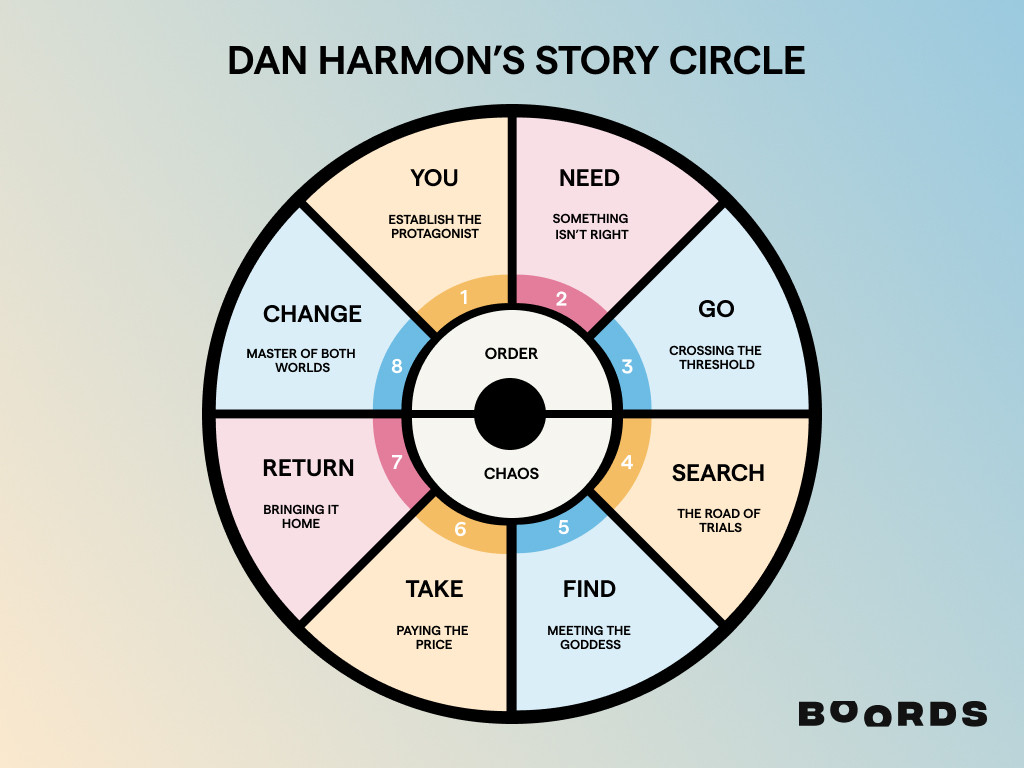

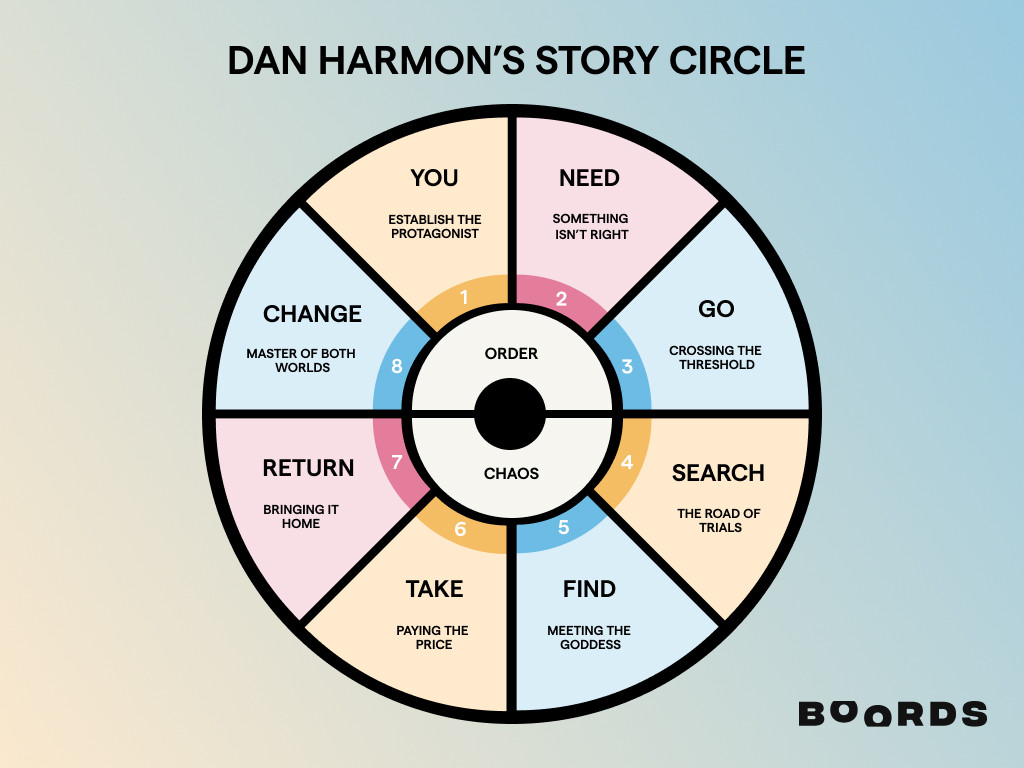

The Dan Harmon Story Circle describes the structure of a story in three acts and with eight plot points, which are called steps. When you have a protagonist who will progress through these, you have a basic character arc and the bare minimum of a story—the story embryo or plot embryo, if you will.

The Story Circle as a narrative structure is descriptive, not prescriptive, meaning it doesn’t tell you what to write, but how to tell the story. The steps outline when the plot points occur and the order in which your hero completes their character development. These eight steps are:

1. You A character in their zone of comfort

2. Need wants something

3. Go! so they enter an unfamiliar situation

4. Struggle to which they have to adapt

5. Find in order to get what they want

6. Suffer yet they have to make a sacrifice

7. Return before they return to their familiar situation

8. Change having changed fundamentally

The hero completes these steps in a circle in a clockwise direction, going from noon to midnight. The top half of the circle and its two-quarters of the whole make up act one and act three, while the bottom half comprises the longer second act. In their consecutive order, the Story Circle describes the three acts:

- Act I: The order you know

- Act II: Chaos (the upside-down)

- Act III: The new order

Working with the Story Circle enables you to think about your main character and to plot from their emotional state. The steps will automatically make your hero proactive as you focus on their motivation, their actions and the respective consequences.

Boords is storyboarding software built for studios & agencies

Create consistent storyboards fast, iterate quickly, then share for feedback.

Try Boords FreeThe Story Circle in story structure theory

Why is this narrative structure a circle? A classic graph of the three-act structure charts the rising and falling action with its plot points as a line with peaks, so why can't your hero complete the eight steps in a linear fashion from the beginning to the end?

The Hero’s Journey

Dan Harmon hardly invented the circular narrative structure or traced the cyclical nature of stories in the three-act structure. He merely simplified the Hero’s Journey and adapted it to his own screenwriting needs. The hero’s journey is a template of stories that describes the stages of a hero embarking on a quest or adventure, who has to go through crisis before victory to emerge transformed. Though the hero often brings back an “elixir”, the solution to their initial “problem”, it’s their inner change that enables them to prevail in the “new order” at home.

The monomyth

The return as expressed in the circle is essential to the monomyth, which is a concept of mythology described by the American writer Joseph Campbell in The Hero with a Thousand Faces. The monomyth sees common narrative structures in all great myths. Campbell names the three acts Departure, Initiation, and Return, and charts the Hero's Journey over 17 stages. Hollywood executive and Disney screenwriter, Christopher Vogler, reduced the number to 12 steps in The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure For Writers.

Simplification of steps in the circle

Interestingly, American philologist David Adams Leeming in 1981 and American screenwriter and filmmaker Phil Cousineau in 1990 both used only eight steps for their adaptation of the Hero’s Journey. Dan Harmon developed his Story Circle in the late 1990s when he was stuck on a project. He cites Christopher Vogler and the screenwriting author Syd Field as influences.

The Hero’s Journey in screenwriting

The Hero's Journey, the monomyth and Joseph Campbell are popular in Hollywood filmmaking. George Lucas used the template for Star Wars, you can read The Matrix trilogy by the Wachowskis as an extensive study in mythological storytelling, and Pixar movies such as Finding Nemo exhibit monomyth story structure.

Save the Cat

Screenwriter and author Blake Snyder omitted the circular structure in his work, but his book Save the Cat! The Last Book on Screenwriting You'll Ever Need also takes the Hero’s Journey and breaks it down into 15 essential story beats or plot points.

What else is Dan Harmon known for?

Daniel James Harmon (born 1973) is an American writer, producer, and actor known for the sitcom Community and the animated series, Rick and Morty. In episode S4E6 “Never Ricking Morty” the two characters find themselves aboard the circular Story Train and the episode pokes meta-fictional fun at the narrative structure. Dan Harmon also created and hosted the comedy podcast Harmontown. In 2013, Harmon published the book, You'll Be Perfect When You're Dead.

The 8 steps of the story circle

You. Need. Go. Struggle. Find. Take. Return. Change. The way the story circle works is that your main character, much like Campbell’s hero, moves from a zone of comfort towards a want, and with that, into the chaos of the second act, from where they’ll return changed. The top half of the circle represents order and the bottom half chaos. The right side of the circle represents the hero resisting their transformation, the left side represents the hero moving towards their transformation.

In this cyclical nature of storytelling, you can see the main character gain and lose: they gain their want, but lose stability; they lose in the struggle, but ultimately find what they want; they pay a heavy price for it, but can bring it back home; the old order cannot be again, but they have changed to exist in the new order.

1. A zone of comfort

The first step establishes the hero of your story in their familiar surroundings. Think of it as a 'before' picture. Note that "zone of comfort" doesn't mean things are perfect. Your main character exists in a status quo in which they have arranged for themselves to fit into their current conditions.

The 'before' picture is important for the character arc so that viewers can recognize the significance of the change later. Interesting main characters are not perfect, either, but exhibit human flaws the audience can understand and sympathize with.

2. Desire

For the second step, you dangle something in front of your main character: desire is something they want as a thing to obtain or a problem they want to go away.

The desire becomes the main goal of the protagonist, but their next actions are decided in a "push" or "pull" fashion: if the desire is pulling them out of the status quo, then they might prepare for the journey (think: Harry Potter getting his supplies). If they're being pulled out of their comfort zone and would rather stay where it's nice and warm, then they debate how they can avoid having to go.

"Desire" can take the form of a problem or an adversary in the sense that the hero would very much like for the antagonist to disappear so they could return to the status quo right away.

3. Entering an unfamiliar situation

In step three, you kick off the action: green means go! Your hero is proactive: even when they've been debating and their desire is of a "pull" nature, they still make a conscious decision and take the first step themselves. This step also signifies the crossing of the threshold from order into chaos, from the first into the second act.

Their new surroundings are unknown and they find themselves in an unfamiliar situation, which can be hostile, or simply something they’ve never experienced before: it’s the figurative (or, with Stranger Things, literal) upside-down of their initial surroundings.

4. Adaptation

Your hero may or may not like the chaos in their new world, but the only way out is through. As a storyteller you throw increasingly bigger obstacles in their way and put them through many trials and tribulations, forcing them to adapt as they struggle to overcome the hurdles.

What's important: the way back is barred, because the old home is so much worse (up to where return signifies death), or because there is another insurmountable concrete or abstract obstacle.

5. Attaining the object of desire

At the halfway point, you let your hero have what they desire. Reading the Story Circle like a clock, it's now 6 PM and high time to return home. Step five, as the crucial finding step, raises the stakes of the story.

Your main character has completed the search, found what they wanted, and is holding the (metaphorical) key in their hands — but the lock which it turns is half a world away! Can they make it back, and in time? To increase tension, many stories introduce time constraints here, such as a countdown of any sort, a sick or wounded companion, or the environment turning on the main character.

6. A heavy price to pay

Your hero takes what they want, but something is taken from them. Before they can go on, they must leave something behind. This loss can take many forms: a temporary, albeit despairing setback which leaves the hero stranded; the death or sacrifice of a companion character; losing "innocence"; having to give up any integral part of themselves, from limb to memories.

This step marks the absolute low point in the journey of your hero. The heavy price is so hefty that they seriously doubt if carrying on is even worth it. There are many names to describe this moment, from figurative death (of the old hero) to the “dark night of the soul” or the darkest hour.

7. Return to the familiar situation

Your hero finds it within themselves to complete the journey and return home to their familiar situation. However, within themselves is key here! Note that with step seven, your main character crosses back into the upper half of the circle, leaving the chaos of the second act behind. Yet this threshold doesn’t come without a trial of its own.

In ancient myths, when the protagonist returns, they often face a gatekeeper, a riddle to solve, or proof that they are who they say they are. Although they surely have changed externally, it’s their internal transformation that allows them to pass this test. Even when the magic “key” is a concrete object, such as an “elixir”, only they can wield or apply it.

The familiar situation is often only seemingly familiar and externally changed as well, because the hero has been presumed dead, their old surroundings have been transformed or old friends have moved on with their lives.

8. Fundamental change

The application of the “solution” by your hero to establish the “new order” brings with it the realization that they are not the same person anymore: they have changed from the beginning. This is where you do a second snapshot and show the ‘after’ picture.

Change can be for the good and your main character is now wiser, better, more mature, no longer alone, or richer in some sense; but the ending can also be tragic, and though they have brought better circumstances for someone else, they are now morally corrupt, filled with despair, utterly alone, or at the end of their life.

Get your FREE Filmmaking Storyboard Template Bundle

Plan your film with 10 professionally designed storyboard templates as ready-to-use PDFs.

How to use Dan Harmon’s Story Circle

In conclusion, let’s note again that Dan Harmon’s Story Circle, like all story structures, is best understood as primarily descriptive; approaching screenwriting with such a ‘template’ seems formulaic, but the structure doesn’t prescribe to you as a writer the story to tell, only how. You can take Snyder’s beats or the Dan Harmon Story Circle and overlay the structure over any existing film (with a story in the traditional sense): from Harry Potter to anime movies to early cinema, you’ll be able to match the steps to the action or the script.

As a screenwriter working on a feature film, TV series or TV show, you can begin plotting the character arc of your hero with the eight steps we’ve outlined above. Gather your ideas and see what sticks, or test an existing story idea with the eight steps: are your stages ‘strong’ enough? Pay attention to the three quarters, or noon, 3 pm, 6 pm, and 9 pm, when you read the Story Circle like a clock. They’re essential to moving your story forward in a believable way.

If your story doesn’t seem to pick up any momentum and you struggle to progress your main character through the steps, you might need to work on your hero more. Are they proactive enough? Is their desire big enough? Are the upper and lower half of the circle opposites, and are the left and right half contrasting enough?

For more theoretical background, you can read up on the Hero’s Journey by Joseph Campbell, and for a fun, practical exercise, watch a favorite movie and plot the steps of Dan Harmon’s Story Circle for it!