What is a Tracking Shot? Definition & Examples

- What is a tracking shot in filmmaking?

- Examples of tracking shots in movies

- How to shoot a tracking shot

In the world of film, a tracking shot stands out as a dynamic technique where the camera moves alongside the action, often for a substantial duration. This method can intimately follow a character or object, or offer a wider perspective on unfolding events. Originally, the tracking shot referred to cameras moving on physical tracks in old Hollywood, defining the original tracking shot concept. Today, it refers to any prolonged camera movement. A good tracking shot is memorable, immersing viewers in the film and often becoming an iconic part of cinema history.

But what differentiates a tracking shot from a dolly shot? And what are some of the most memorable uses of this technique in movies? Additionally, what equipment is needed to create your own effective tracking shots? Let's explore these questions in more detail!

What is a tracking shot in filmmaking?

A tracking shot, a dynamic element in film and TV, involves the camera moving through a scene. This movement allows for following characters, showcasing action, revealing landscapes, or simply creating a sense of dynamism. Common in various productions, great tracking shots are pivotal in capturing everything from cinematic narratives to intense sports events, drawing viewers into the environment.

Distinct from static shots, panning, or tilting, a tracking shot offers the camera freedom to move through space. While panning and tilting involve rotating the camera around its axis, tracking shots are about physical movement. Stabilization is key for smooth footage, though intentional jitters can be used for effects like simulating running or an unstable environment.

These shots are typically longer, filled with action or detailed visuals, demanding significant planning and coordination. A long tracking shot, in particular, can bring a unique dimension to a scene, often becoming a memorable part of the cinematic experience. Challenges include choreographing scene elements, maintaining focus on the desired action, navigating around obstacles, and managing aspects like lighting, sound, and continuity.

Often forming a long take, tracking shots can extend beyond ten minutes, creating a flowing, uninterrupted narrative. Though traditionally linked to cameras on physical tracks, modern tracking shots employ various methods and equipment, moving in any direction and dimension. They can follow a subject, capture action, or traverse randomly through a scene. Filmmakers may also combine multiple shots seamlessly to create an extended sense of movement.

Great tracking shots reward viewers with their immersive nature. They can bring the audience along with one or more on-screen characters, provide a point of view amid all the action, build up to a climax or arrival, convey emotion, or develop the story in real-time.

Ultimately, a tracking shot's immersive nature rewards viewers, offering a journey-like experience, building climaxes, conveying emotions, and unfolding stories in real-time.

Brief history of the tracking shot

The tracking shot, a staple in modern cinematography, owes its existence to the evolution of camera technology and stabilization methods. Initially, early cinema was constrained to panning and tilting using tripod-mounted cameras. However, the 1914 film Cabiria by Giovanni Pastrone introduced one of the earliest instances of a slow tracking shot, marking a significant milestone in film history.

Hollywood has historically coined specific terms for camera movements. A key development was the camera dolly, a wheeled device that allows smooth movement of the camera. This innovation led to the differentiation between tracking and dolly shots. Originally, a tracking shot indicated lateral movement, where the camera would "track right" or "track left", while a dolly shot involved moving inwards ("push in") or outwards ("pull out").

Modern cinematography has refined these terms. Today, a dolly shot typically involves an actual dolly, and lateral movements are referred to as trucking shots, with terms like “truck right” and “truck left”. The versatility of tracking shots has grown with diverse equipment such as Steadicams, cranes, gimbals, vest stabilizers, drones, and handheld cameras. A notable example of innovation is Jean-Luc Godard's use of a handheld camera from a wheelchair for his 1959 French New Wave film "Breathless". This evolution of camera movement techniques has led to some of the best tracking shots in cinema, showcasing the artistry and technical prowess of filmmakers.

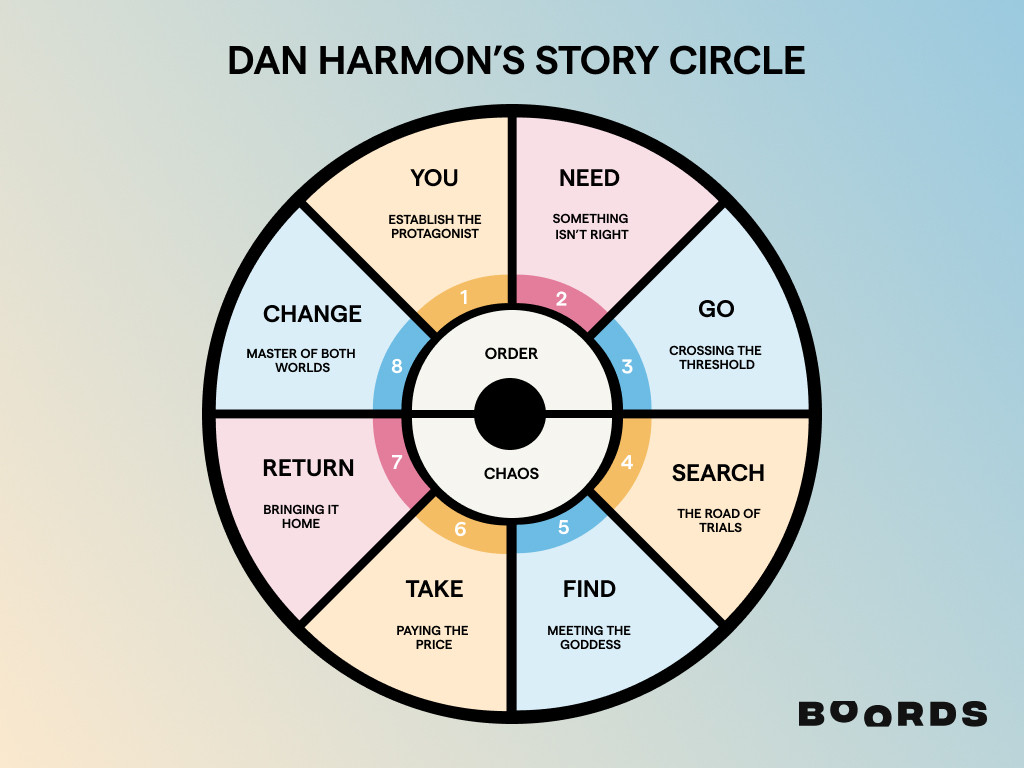

Boords is storyboarding software built for studios & agencies

Create consistent storyboards fast, iterate quickly, then share for feedback.

Try Boords FreeExamples of tracking shots in movies

Let's explore the art of tracking shots through Hollywood's lens across different eras. Here are 10 standout examples of some of the best tracking shots in movie history, showcasing exceptional on-screen storytelling.

Goodfellas

In Martin Scorsese's GoodFellas (1990), a narrative revolving around mobster Henry Hill, his wife Karen, and his criminal associates, there's a particularly notable tracking shot that has captured the attention of cinephiles worldwide. This iconic shot unfolds as the couple makes their way into the Copacabana Club. It starts with a close-up of the car keys, then transitions to follow them inside. Throughout this scene, the tracking shot predominantly trails the characters, subtly shifting to convey Karen's perspective. This masterful use of the tracking shot immerses the viewer in Karen's sense of awe and curiosity, culminating in her pivotal question, "What do you do?" This scene is a textbook example of how a tracking shot can enhance storytelling by aligning the audience's experience with a character's journey.

Touch of Evil

In the opening scene of Orson Welles' Touch of Evil (1958), a crane shot brilliantly captures the tension. The camera follows a car with a ticking bomb in its trunk, intermittently leaving the frame to build suspense about its next appearance and the potential victims. The explosion, happening off-screen, leaves only the burning wreck visible, emphasizing that the build-up of tension is as impactful as the climactic moment itself. This technique showcases the ability of the tracking shot to enhance suspense and narrative depth.

Atonement

In Atonement (2007) by Joe Wright, cinematographer Seamus McGarvey skillfully uses a five-minute tracking shot to depict Robbie Turner's harrowing experience at the chaotic Dunkirk evacuation. This camera movement seamlessly weaves through the turmoil, briefly losing and then refinding Robbie in a scene rich with live animals, gunshots, pyrotechnics, and brawls, all set in the challenging landscape of sandy terrain. This tracking shot vividly captures both the chaos of war and the emotional depth of Robbie's journey.

1917

1917 presents a high-stakes mission where two soldiers race against time to deliver a vital message, affecting 1,600 troops. Director Sam Mendes and cinematographer Roger Deakins tell this story in a real-time format, using a series of carefully planned tracking shots to create the appearance of one continuous shot. The longest of these tracking shots lasts over nine minutes, demanding meticulous execution and coordination. This technique, merging multiple tracking shots into a seamless narrative, highlights the film's excellence in single-take cinematography.

Victoria

Victoria (2015), directed by Sebastian Schipper, boldly embraces the concept of "One City. One Night. One Take." as its central theme. This German film, captured by cinematographer Sturla Brandth Grøvlen, is a remarkable feat in filmmaking, shot in a genuine single take lasting 138 minutes. The production navigated through an extensive single take, covering 22 locations across Berlin, primarily between the hours of 4:30 am and 7 am. Out of three attempts, the third take was selected as the final cut, showcasing an extraordinary blend of precision and spontaneity in filmmaking.

The Revenant

In Alejandro Iñárritu's The Revenant (2015), an early and intense fight scene vividly captures a group of trappers ambushed by Arikara Indians. This sequence, predominantly a tracking shot, primarily focuses on Hugh Glass, effectively portraying the chaos and disorder of the battle with danger looming from every direction. Despite the use of digital stitching and CGI, these elements do not detract from the exemplary cinematography by Emmanuel Lubezki. The tracking shot plays a crucial role in immersing the audience in the frenetic and perilous atmosphere of the scene.

Children of Men

In Alfonso Cuarón's Children of Men (2006), the film is notable for its use of tracking shots by cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki. These shots are seamlessly merged to craft extended takes that, from a logistical standpoint, seem nearly impossible. This technique adds a unique and immersive quality to the film's storytelling.

Birdman

Alejandro González Iñárritu and cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, known for their inventive style, brought a unique vision to the 2014 film Birdman. They created the illusion of a single, continuous take by expertly stitching together tracking shots ranging from ten to fifteen minutes. This approach, echoing the technique used in films like "Victoria," Hitchcock's "Rope" (1948), and Alexander Sokurov's "Russian Ark" (2002), showcases their mastery in blending individual shots to create a seamless cinematic experience.

The Shining

Stanley Kubrick's signature use of the long tracking shot is exemplified in The Shining (1980), particularly in the scene where Danny rides his tricycle through the hotel's labyrinthine corridors. This shot immerses viewers in the disorienting, maze-like layout, building suspense up to the eerie encounter with the twins, and effectively sets the tone for the film's chilling atmosphere.

Vertigo

The Vertigo effect, named after Alfred Hitchcock's Vertigo (1958), is a camera technique where the foreground subject appears still while the background shifts dramatically. Achieved with a wide-angle zoom lens and dolly movements, the camera moves forward or backward, zooming in the opposite direction to keep the subject constant as the background alters in size. This technique, a form of tracking shot, is also known as a dolly zoom, push-pull, or reverse-tracking shot.

How to shoot a tracking shot

Shooting a tracking shot involves a blend of technical know-how and creative vision. Here’s a brief guide on the essential equipment and some tips to help you capture compelling tracking shots for your project.

Tracking shots by type of equipment

Below, we'll summarize types of shots according to the equipment cinematographers use for recording:

- Dolly Shot: Involves a camera mounted on a dolly, which moves along dolly tracks for smooth, lateral camera movement, typically parallel to the action, either left or right.

- Steadicam: Utilizes a stabilizer for handheld shots, allowing for fluid tracking movements with a camera stabilizer.

- Camera gimbal: A gimbal is a handheld device enabling the cinematographer to operate a mounted camera with stability. It features a 3-axis stabilizer (pitch, yaw, and roll) for controlled tilt, pan, and level adjustments, independent of the operator's movements.

- Crane shot: This shot uses a mounted camera on a crane or boom, enabling sweeping movements through scenes for dynamic crane shots. For the ending of Twelve Monkeys, director Terry Gilliam famously used a crane upon a crane to record the long tracking shot in the parking lot.

- Drone shot: Drones offer a modern solution for aerial shots, providing stable, versatile, and cost-effective aerial tracking shots with camera-mounted drones.

- Rail shot: Here, the camera is mounted on rails or cables, allowing movement above the action on a predetermined path, often used in large venues like stadiums or concerts.

- Pure handheld: Camera operators can choose to record a tracking shot by hand without stabilization. A handheld shot offers raw and immersive footage that closely follows characters or provides their point of view.

- Car mount: A camera mounted on a vehicle captures scenes either inside or around the moving object, adding dynamic perspective to a tracking shot.

Each of these tools offers unique ways to capture tracking camera movement, enhancing the visual storytelling in films.

Get your FREE Filmmaking Storyboard Template Bundle

Plan your film with 10 professionally designed storyboard templates as ready-to-use PDFs.

Tips for recording tracking shots

Achieving a good tracking shot, a challenging yet rewarding aspect of film production, involves strategic planning and execution. Here are essential tips to help both filmmakers and camera operators succeed in capturing an effective tracking shot:

- Craft a Shot List: A tracking shot should be thoughtfully integrated into your story. Determine the appropriate moments for its use, focusing on which character or perspective to highlight. Planning your shot list in advance ensures that each tracking shot serves a clear narrative purpose.

- Select the Right Equipment: Not all tracking shots require a dolly and tracks. A Steadicam or camera stabilizer often suffices and can be more budget-friendly. It’s crucial for the camera operator to be well-versed with the chosen equipment, ensuring the right lens and focus distance are used for optimal tracking camera movement.

- Scout and Research Locations: Before filming, the camera operator and director should scout the location to identify the best setups for lighting, sound, and camera paths. Marking positions for actors and extras is essential to avoid obstructing the camera’s path.

- Rehearse for Precision: The camera operator should practice the tracking shot, coordinating with actors and crew. Rehearsals help minimize the number of takes needed and ensure a smooth tracking movement. It's important to consider how the background action complements the foreground focus.

- Prepare for Post-Production: Even with the best preparation, some tracking shots may have minor imperfections. These can often be corrected in post-production. Camera operators should ensure that they capture all necessary footage, allowing for seamless editing and transition planning.

By following these steps, you can navigate the complexities of recording a tracking shot, transforming a challenging aspect of production into an opportunity for cinematic excellence.